Accounting is one of the oldest professions. Archeologists have studied financial records that are four times older than the Great Pyramids of Egypt. “Tally marks” were etched into the thigh bone of a baboon 20,000 years ago as a form of “correspondence counting”. Of course, the earliest forms of accounting were relatively slow, insecure, and probably didn't travel very far.

In the Internet era, fintech architects use similar methods to accomplish similar goals, but on a much bigger scale. Today, card networks are lightning-fast: Visa's network can process over 65,000 transactions per second. They are secure: American Express guarantees you will never pay for something you did not buy. And the cards they process are accepted everywhere: how else can I attend the opera in Milan, buy a new suit in Shanghai, and take a cruise down the Nile, and pay for everything with the one plastic rectangle in my wallet - or even just my phone?

Now, it's likely you're here as a fintech or neobank thinking about issuing your own card. So instead of fantasizing about globetrotting (come on, vaccine!), let's take a trip through card networks and how they work.

What is a Payment Network?

A payment network is an association of member banks that facilitates the payment transaction between the merchant and issuer, i.e., the requestor (cardholder to the merchant to acquiring bank) and source (issuing bank) of funds. It's made up of both card networks like Visa, MasterCard, Discover, JBC, and other networks like Zelle (interbank network), Popmoney, Cirrus, Plus, and others.

How Do Card Transactions Work?

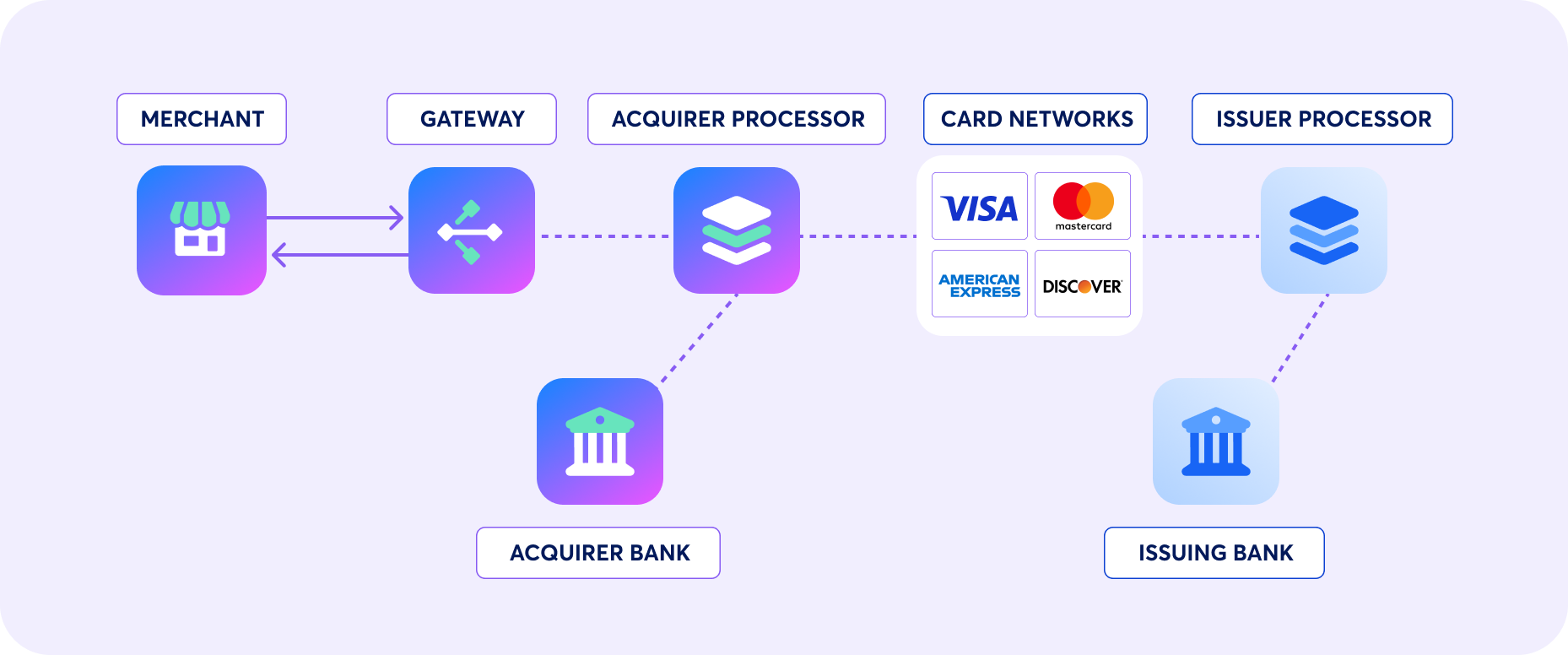

There's a whole ecosystem involved in card transactions, including the issuing bank, (payment) card network, acquiring bank, merchant, and finally, the cardholder.

An “issuing bank” distributes payment cards, sets the cardholder's ability to purchase, manages rewards (credit cards only) or offers, and approves (or declines) purchase requests. An “acquiring bank” processes card transactions on behalf of merchants. Buyers, sellers, and both issuer and acquiring banks communicate via card networks.

When the customer enters their card number on a website and clicks “pay now,” they're asking the payment card issuer (e.g., the bank or credit union) to loan them money for the purchase. At this point, the card network gathers information about the buyer and their intended purchase and sends it to the acquiring bank (or its delegated processor). The acquiring bank then requests payment authorization from the card-issuing bank via the card network. As you can imagine, hackers target payment transactions at high rates.

Securing Card Networks Against Fraud

Card networks take numerous countermeasures to combat fraud. The issuing bank verifies a card's validity based on its number, expiry date, available funds, billing address, and more. Logic plays a role: how often does the cardholder buy a $5,000 coat? Geolocation plays a role: is the cardholder really in Tokyo? A correct billing address and Card Security Code (CSC) may not be sufficient; the card issuer may contact the cardholder to request personal verification, either via challenge questions or multi-factor authentication (MFA).

Card networks seek to protect their communications (and cardholder data) from criminals. Often, networks use a form of data security called tokenization, in which your real card number is referenced only by a “token” and not your actual card number. One physical security measure that you see everyday is on physical receipts, where only the last four card digits are printed, rather than the whole account number.

When an issuing bank decides whether to approve or decline a transaction, a response is sent back to the acquiring bank and then to the merchant. Other delegated intermediaries may include a payment service provider, payment gateway, or payment processor. If the issuer approves the purchase, the merchant receives authorization and will provide the customer with a receipt to complete the sale. If a transaction appears fraudulent, the issuer will decline it and may place a temporary hold on the card. After all, they do not want to get stuck with a bill for something the cardholder did not intend to buy or cannot afford.

Back to How it Works

A card network gets all parties singing from the same sheet of music, and the basic transaction approval process takes only a few seconds. All approved authorizations are routed via the card network for clearing and settlement at the end of each business day. At that point, issuing banks place a hold on the amount of each purchase on each cardholder's account.

Once the issuing bank receives a final confirmation of a successful transaction, it transfers the funds to the acquiring bank, less an “interchange fee,” generally within 1-2 days. The issuing bank also posts the transaction information to the cardholder's account, and the cardholder receives a billing statement which they are legally obligated to pay in full. The acquiring bank then credits the merchant's account for the purchase price, less a 2-5% “discount fee” for its service.

Who are the Card Networks?

There are four major credit card networks: Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover. Visa and Mastercard are simply credit card networks. They connect merchants with their customers' financial institutions and are called “open networks” because they allow many different types of financial firms to participate. AmEx and Discover are credit card issuers and credit card networks; they process transactions, approve purchase requests, and are called “closed networks” because fewer firms can participate on the network.

Ultimately, any card network's goal is the same: to create a fast, secure, easy-to-use, and reliable way for cardholders to make purchases so they can win consumer trust and grow participation in their network.

If you would like to learn more about card networks and issuing payment cards, VGS has you covered.