Explore how to manage infrastructure environments at scale using Terraform and Terragrunt. We unpack the challenges of blast radius and time-to-deploy, and propose a solution that combines the benefits of both tools while minimizing statefile size and reducing plan and apply times.

Prelude - IaC at VGS

VGS has had a long and varied relationship with different IaC solutions over the course of the company. Way back in 2016 when we first started out, VGS was a CloudFormation shop and built the first implementations of our KMS, VPC, and proxy infrastructure successfully with AWS CloudFormation and some Troposphere to help glue things together. Over time we discovered gaps within CloudFormation for newer AWS services and non-AWS services created a need to explore alternative IaC solutions.

On this journey we've mostly settled on Terraform with the help of Terragrunt with a small dabbling of AWS CDK and bazel along the way. Ultimately we've settled on moving all of our IaC to Terraform as we've found this well supported and liked across both the wider community and our infrastructure team.

As part of this journey we've started to pay close attention to how we model our IaC modules and components and discovered some interesting facts and findings that we wanted to share with the community.

Summary

Terraform has emerged as the de facto standard for managing infrastructure as code. Terraform’s modules give you the ability to eliminate much repetitive code, like software functions. By creating higher-level modules that use multiple lower-level modules, and those higher-level modules into final configurations, you get great composition, weaving together smaller modules into larger ones.

Those larger modules and configurations make single-step deployments and updates easy, but expand the blast radius significantly, while growing the time-to-deploy to intolerable amounts.

Terraform’s "border of execution" is the configuration or module on which you execute terraform apply. This is the level at which the statefile is managed, leading to both the blast radius and time to execute.

Terragrunt, among its other features, attempts to solve the blast radius and time to execution by linking together multiple modules and their dependencies, but without joining them into a single statefile. However, Terragrunt’s native tree structure creates its own DRY issues that increase at scale.

We search for a solution that solves DRY at both levels, while enabling statefiles of the minimal necessary size, so that it is possible to reduce plan and apply times to the minimum necessary.

Structure

The structure we will use is typical to many organizations. We start at the bottom and work our way up.

Infrastructure is made up of individual resources, e.g. S3 buckets, VM instances, EKS clusters or DNS domains and records. Although most Terraform examples simply bind a few of each of those together into a configuration and deploy it, in the real world, groups of those normally are bound together for a single deployment purpose. For example, our "secure communication service" could be composed of: 2x S3 bucket, 1x AWS FTP Transfer, 2x Lambda to process, 1x SNS notification. Terraform natively supports grouping these together into a single grouping via reusable "modules".

For some environments, that is sufficient. Production is made up of 1 "secure customer communication service", one Kubernetes cluster and one EC2 ASG.

However, most environments of any scale and/or complexity have an additional layer. Several services are grouped together to be deployed in a uniform "stack". For example, our "customer services stack" could have our "secure communication service" plus "customer email service" plus "voicemail service", while our "payments processing stack" has "credit card payments service" and "bank transfer service". A different purpose for grouping might be by security, e.g. a "secure" (or in-compliance-scope stack) and a "normal" stack. Another purpose is by region. Thus, you might have three instances of the "secure transaction processing" stack in one region and two instances in another, but only one instance of the "common-per-region services" in the "regional" stack, and one "global" stack.

We need stacks because in some environments we may deploy one instance of "customer services" and two of "payments processing", while in another environment we may deploy no "customer services" and three of "payments processing". This pattern is quite common.

Each stack looks identical to every other instance of that stack, except for those options that can be configured via variables, for example, the specific VPC, or the size of instances.

Finally, we have one or more environments, each with a name.

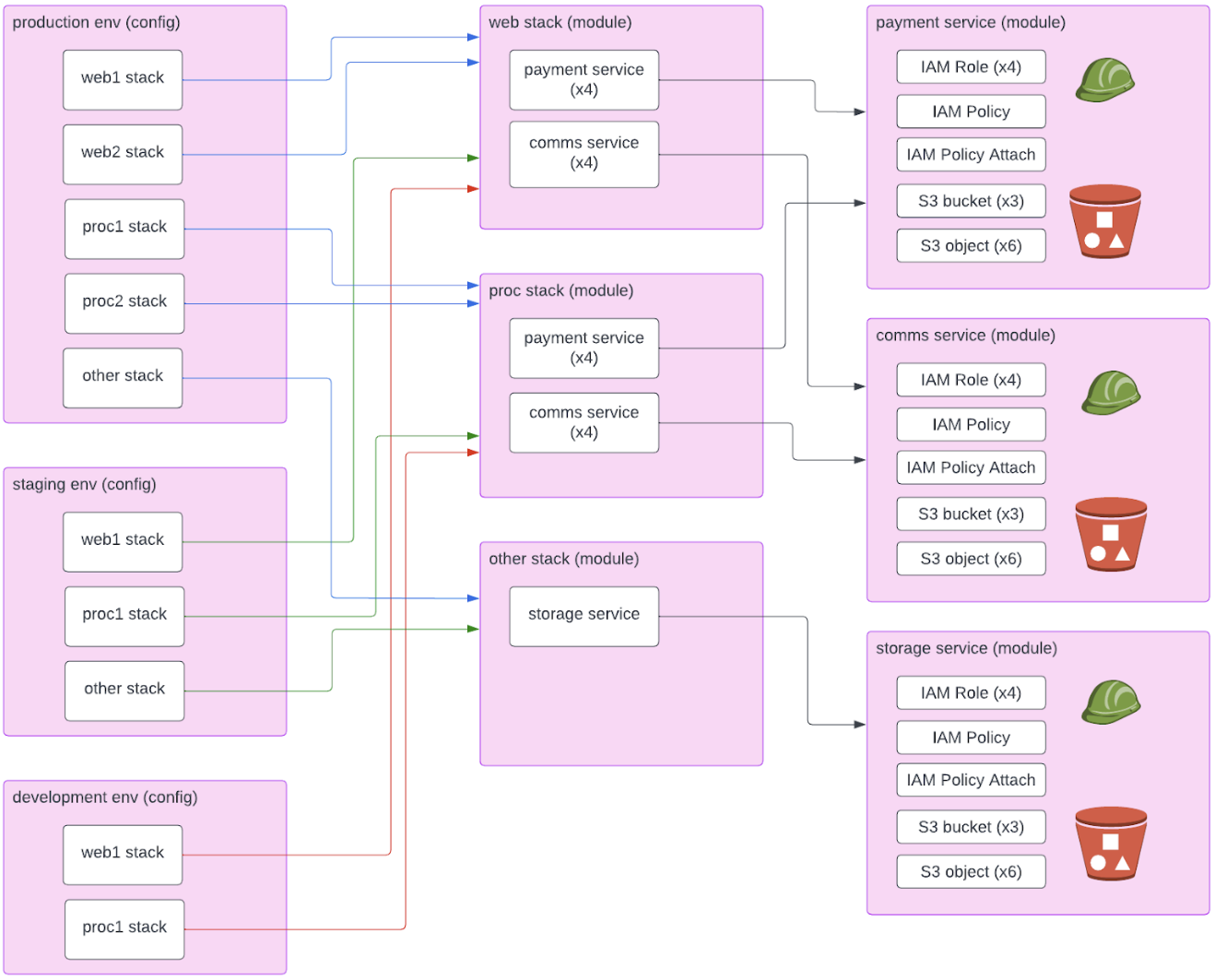

We can describe this as saying that the environments compose stacks, and stacks compose services.

To make this concrete, we create an example with the following:

- Three environments: "production", "staging", "development".

- Four stacks: "processing", "regional", "global", and "web".

- Several services in each stack.

The "production" environment has four instances of "processing" (two each in us-east-1 and us-west-1), two instances of "regional" (one each in us-east-1 and us-west-1), one instance of "global", and four instances of "web".

Implementation

In a pure Terraform structure, we would have:

- One module for each service

- One module for each stack, which includes the services in that stack

- One configuration for each environment, which includes the stacks in that environment

It might look something like this:

// production/main.tf

// contains only references to modules that are stacks

module "processing_us_east_1" {

source = "ref/to/processing"

// parameters

}

module "processing_us_east_2" {

source = "ref/to/processing"

// parameters

}

module "processing_us_west_1" {

source = "ref/to/processing"

// parameters

}

module "processing_us_west_2" {

source = "ref/to/processing"

// parameters

}

module "regional_us_east" {

source = "ref/to/regional"

// parameters

}

module "regional_us_west" {

source = "ref/to/regional"

// parameters

}

module "global" {

source = "ref/to/global"

// parameters

}

module "web1" {

source = "ref/to/web"

// parameters

}

module "web2" {

source = "ref/to/web"

// parameters

}

module "web3" {

source = "ref/to/web"

// parameters

}

module "web4" {

source = "ref/to/web"

// parameters

}

Some stacks then would look as follows:

// processing/main.tf

// contains only references to modules that are services

module "ec2_gateway" {

source = "ref/to/ec2"

// parameters

}

module "ec2_ids" {

source = "ref/to/ec2"

// parameters

}

// etc.

Terraform handles the above very well, composing service modules into stacks, and stack modules into environments.

Further, deploying or updating any one environment is quite simple:

$ cd environments/production

$ terraform apply

However, as the number of services in a stack increases, or the number of stacks in an environment increases, the size of the per-environment statefile grows, and with it, the time to run a terraform plan or terraform apply.

If not for the statefile size and time-to-run issue, this structure would be quite good. There still are configuration limitations to Terraform that Terragrunt solves, but overall, this structure works well. However, the time-to-run issue is a deal-breaker for almost everyone.

The standard solution to this issue is to have more smaller statefiles. The "execution boundary" of the Terraform configuration becomes smaller, down to individual stacks, such as "processing" or "web". If the stacks are big enough, there isn’t much of a choice but to go to the individual service level, such as "secure communications service" or "bank payments processing". Each service is composed of multiple cloud provider resources, so even this is not single-resource statefiles.

Separating statefiles, or more correctly separating configuration boundaries, creates three problems.

First, you lose Terraform’s inherent dependency graph. If Terraform itself no longer is responsible for passing the output of module A to module B, as these are run separately, it no longer knows that B depends on A, and thus to complete A before B. Terraform’s dependency graph is advanced and robust, and is relied upon heavily for exactly this purpose.

Second, and related to the first, it makes it harder to link between what previously were two parts of the same configuration. For example, if you want to pass IAM roles created in one service to the EKS cluster created in another, or the S3 bucket created in one service to the applications created in others.

While there are solutions for these issues, for example reading data from the other module’s statefile, these generally are brittle.

Third, you lose the composition effect. Actually executing the 5 services that previously made up a stack becomes an exercise in recreating the list of what to run. That in and of itself means defining the interrelationships elsewhere, and engineering all sorts of solutions to ensure they all run.

All of this is a pity, as Terraform inherently provides the language to connect various modules, create interdependencies, and determine the execution graph.

Enter Terragrunt

Terragrunt is a Terraform wrapper. It provides the ability to define dependencies between various Terraform configurations, or modules, and execute them together or independently. Whereas Terraform’s native execution boundary, including statefile, is set by the top-level configuration on which you call plan or apply, and you must continue to run it at that level, Terragrunt lets you set lower-level boundaries, and tie together multiple executions of Terraform at those lower-level boundaries. It calls Terraform multiple times in the correct order, passing results between them.

In this respect, Terragrunt is "Terraform-if-it-could-separate-statefiles", or perhaps "Terraform-if-it-could-execute-part-of-statefiles".

This sounds like a panacea, but it is far from it.

In separating the modules, Terragrunt itself requires some structure to indicate its own concepts of "modules", although it does not call them as such. At the lowest, or leaf, level is a reference to a configuration meant to be executed by Terraform. These are then bound together.

Terragrunt implements this module tree as a directory tree. Each directory contains its own terragrunt.hcl file. These are then executed, either individually or multiple together.

If we were to build the above architecture, where the boundary of statefile is our individual services, we would represent our production stack in Terragrunt as follows. We only expand web1, web2, web3 and web4 to demonstrate.

environments/

production/

us_east_1/

regional/

processing1/

processing2/

web1/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

web2/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

web3/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

web4/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

us_east_2/

regional/

processing1/

processing2/

web1/

web2/

global/

Each terragrunt.hcl would import the specific modules, for example the serviceA module or the serviceB module.

Already you can see that although we do not repeat the contents of the serviceA or serviceB terraform modules, we do have to recreate the entire tree structure of each "web" stack, and each "regional" stack, and each "secure" stack, in order to get the statefile execution boundary.

If we then look at also having our "staging" environment, it gets worse:

environments/

production/

us_east_1/

regional/

processing1/

processing2/

web1/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

web2/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

web3/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

web4/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

us_east_2/

regional/

processing1/

processing2/

web1/

web2/

global/

staging/

us_east_1/

regional/

processing1/

processing2/

web1/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

web2/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

web3/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

web4/

serviceA/

terragrunt.hcl

serviceB/

terragrunt.hcl

us_east_2/

regional/

processing1/

processing2/

web1/

web2/

global/

We just duplicated not only everything in web1 into web2 and web3 and web4 inside production, we also duplicated the entire production into staging. Sure, some of the parameters may be different, but this hardly is DRY. It is guaranteed to lead to human error.

In the end, all we are trying to achieve is the following combination:

☐ Set the execution boundaries to manageable scale

☐ Compose together services into reusable stacks

☐ Compose together stacks into reusable environments

Terraform is great at numbers 2 & 3 and terrible at number 1, while Terragrunt is great at number 1, and weak at numbers 2 & 3.

Solutions

How do we solve this problem?

We have several options, and although none of them is perfect, one does stand out.

Use Terraform

One option is to accept that we cannot have all 3 of our goals, so accept the loss of statefile execution boundaries in order to get strong composition.

We go back to our original pure Terraform solution and use it. Sure, it will take a long time, possibly a very long time, to run, but human error likely is avoided, and it is much easier to reason about it.

| ❌ Set the statefile execution boundaries to manageable scale |

| ✅ Compose together services into reusable stacks |

| ✅ Compose together stacks into reusable environments |

Use Terragrunt

Similarly, we could accept that we cannot have all 3 of our goals, so accept the loss of composition of services into stacks and stacks into environments in order to get strong execution boundaries.

We go back to our second attempt, using Terragrunt. It means a lot of copy-paste, but the boundaries are well protected.

| ✅ Set the statefile execution boundaries to manageable scale |

| ❌ Compose together services into reusable stacks |

| ❌ Compose together stacks into reusable environments |

Constrained Terraform

The heart of our issue is that we want Terraform’s composition, including its language and dependency graph, at higher levels such as stacks and environments, but want it to constrain its "execution boundary", especially the parts that involve communicating with the cloud provider, to lower-level components.

Our proposed solution is to remain within the Terraform space, leveraging its native dependency linking language and graph resolution. To do this, without invoking the cost, we need to understand which part of this is expensive.

Martin Atkins, aka apparentlymart, detailed the stages of terraform plan in this StackOverflow response. We highly recommend reading it and not relying on our summary here.

In short, Terraform gets data from 3 places to determine what actions to take:

- The previous state for the entire execution context from the statefile; this is inexpensive.

- The current state for the entire execution context from the cloud provider, a.k.a.

refresh; this is very expensive. - The desired state, or graph, for the entire execution context from the config; this is inexpensive.

With the above states in hand, Terraform compares the desired state (3) to the current state (2) and determines its execution plan, followed by applying the changes.

Why is the second state, refresh to get the current state, so expensive? The reason large configurations with small changes take a long time is that it takes a long time to check on each and every resource from the cloud service provider. This is the heart of the issue.

What about calculating the desired state, i.e. the graph? Is that truly inexpensive? While this can take time, a modern computer, even a small cloud instance VM, can do even large graphs in memory very quickly. Is it possible to make a configuration so large that even the graph calculation takes a long time? It certainly is. That is likely to be a tiny minority of the use cases, and thus out of scope for our solution.

I recently worked with a brilliant engineer, Jon Johnson, to optimize an open source graph implementation. Of course, "worked with" means that I just described the issue and location, and Jon brilliantly figured out the problem and did the optimization work in a few days. A graph of around 600 nodes and 10-15,000 edges used to take 6+ minutes to calculate; when done, it was under 2 seconds.

The apply itself actually is very efficient; once the current state and the desired state are known and the differential calculated, it only needs to update the specific changed resources. It is the plan that is expensive, and specifically the fact that plan gets the current state for the entire statefile.

In principle, this is good. We do sometimes want to be able to check the actual current state of the entire execution context against the desired state. The issue is that we do not always need to be able to do it. Actually, the majority of the time we do not. This distinction is at the heart of how Terragrunt manages its state. If you run terragrunt --run-all at the highest level, it calls terraform plan (and hence refresh) for all the resources. Normally, however, you just run it at the level you care about, where changes were made.

By limiting the refresh to just the changed resources, we keep the inexpensive entire graph calculation, while limiting the expensive cloud lookups.

| ✅ Set the statefile execution boundaries to manageable scale |

| ✅ Compose together services into reusable stacks |

| ✅ Compose together stacks into reusable environments |

Implementation

What do we need to make this happen?

- A way to limit

refreshandapplyto smaller components. - A way to calculate which components have changed between last run and desire skipping current.

Limit Execution

First, we need a way to limit refresh and apply to smaller components. Fortunately, Terraform has this part solved.

Terraform has an option to refresh, plan and apply only specific parts of its dependency graph; see this document. We execute the highest level, i.e. environment, but pass it a subset of the composition to run, using one or more -target.

For example, we could run Terraform to plan just for serviceA in "web1" and "web2" stacks.

$ terraform plan -target module.web1.module.serviceA -target module.web2.module.serviceA

Terraform calculates the entire dependency graph to get the desired state, as we would want it to, and already has the previous state in the statefile, but runs refresh to get the current state, just on module.web1.module.serviceA. If that in turn depends on other upstream resources, it will check those as well, but it will not go downstream.

The main challenge that remains is determining exactly which resources to target.

Determine Changed Components

Ideally, Terraform itself would support this without the need for -target. Terraform already knows how to read the configurations to generate the desired state, the statefiles for the previous state, and calculate changes to be applied. It also has the option to run terraform plan -refresh=false, although that disables all refresh.

What we actually are looking for is for Terraform to do the following:

- Read the previous state from the statefile - it already does this

- Create the desired state from the current configuration - it already does this

- Calculate which resources have differed between previous and desired - this is different, where currently it calculates those only against the current state, based on refresh

- Run

plan, includingrefresh, targeting only those resources calculated in the previous step

Unfortunately, Terraform does not natively have a mode that automatically figures out and executes plan or apply on changed files only, something like:

$ terraform plan -changed-only

Our proposal is the following:

- Run

terraform plan -refresh=false. This should give the list of items to update comparing "last run state" and "desired state", without connecting to the cloud provider. - Retrieve the list of resources that would be affected from the plan output. For example, those to be changed are

modules.web1.modules.serviceAandmodules.web1.modules.serviceB. - Run

terraform plan -refresh=true -target <changed>. This should give a plan based on comparing the current state and desired state of those modules. - Run

terraform applyusing the plan output from the previous step.

Challenges:

- Step 2, retrieving the list of changed resources. This is not natively built into the Terraform CLI and will require some work.

- Step 3, running plan

-target. Generally, the list of targets is small. If a large number of resources has changed without a common tree, it will not fit onto a command-line.

The above may require building an additional tool which uses Terraform’s library surface, which is less than optimal.

Performance Analysis

How well does this work?

This is not a complete, proper, large-scale statistical analysis. Instead, this is a single run to determine rough numbers for the scale of improvement.

We created a Terraform configuration composed of several stacks, each of which has several services, each of which has several resources, for a total of just under 600 resources. To save on cost, we used IAM Roles and Policies and S3 buckets, as these have near-zero cost to create, but nonetheless require communication with the cloud service provider and time to resolve.

The source is available on github.

We deployed the configuration as is, which took several minutes.

We then changed a single s3 bucket object in each of 3 buckets, in a single service in a single stack, and ran terraform plan ten times each in several modes:

- Regular

terraform plan, which calculates the entire graph and requires resolution with the cloud of all ~600 resources. - Without refresh, i.e.

terraform plan -refresh=false, which calculates the entire graph but requires resolution with the cloud of just the s3 bucket objects. - Constrained

terraform plan -target=<service-affected>, which calculates the graph and refreshes, but just for the service affected (root). - Constrained

terraform plan -target=<resources-affected>, which calculates the graph and refreshes, but just for the individual resources.

The results were as follows.

| Mode | Time (average s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Regular plan with refresh | 109.51 | Broad spread, from 0:58 to 3:20 |

| Regular plan without refresh | 5.7 | Consistent across number of resources changed |

| Constrained plan with refresh target for service | 8.9 | |

| Constrained plan with refresh target for resources | 8.5 |

We did not run terraform apply, as the cost will be the same in all scenarios. It only applies the resources that need changing.

We do not see much difference between running plan -target <service> and plan -target <resources>, as there are few unchanged resources in the service. If only 3 resources out of 100 in a service were changed, i.e. 97 additional to be checked, we would expect a big difference.

Conclusion

Using Terraform alone to create the proper dependencies among resources and taking advantage of its graph, while limiting the plan stage just to changed resources, can significantly improve the performance of Terraform. Specifically, it makes it as efficient as Terragrunt, without the proliferation of statefiles and complex repeated code.

To be clear, Terragrunt still has a strong role to play in managing the various areas in which Terraform is weak, such as certain templating and duplication at earlier stages, all of which are beyond the scope of this article.

We have not yet investigated several outstanding issues, specifically, how Terraform's parallelism will be affected, and how to handle when the list of changed resources increases to more than a few, overwhelming the command-line. However, we believe we have a solid solution for managing infrastructure environments using Terraform at scale.